What is scar therapy (and why is it important)?

Ok, I’ll start with the second half of this question, to give you a bit of background:

About one in two people have a scar; a study of 11,000 people from China, Russia, the USA, Brazil, and France found that 48.5% of individuals had a scar, and I see no reason why this proportion would differ drastically in other countries - yes, we could argue about the availability of surgical procedures, but the majority of the scars reported in that study were from an accident…. and those can and do happen anywhere.

Here’s the thing: scar tissue, as in the actual fibres that were damaged and repaired, is at best only 70% as functional as non-scar tissue. Think: reduced movement, increased risk of injury, and pain. And that 70% is the best case scenario! However, uninjured tissues surrounding the scar can very much be affected by the scar - we’ll get to that.

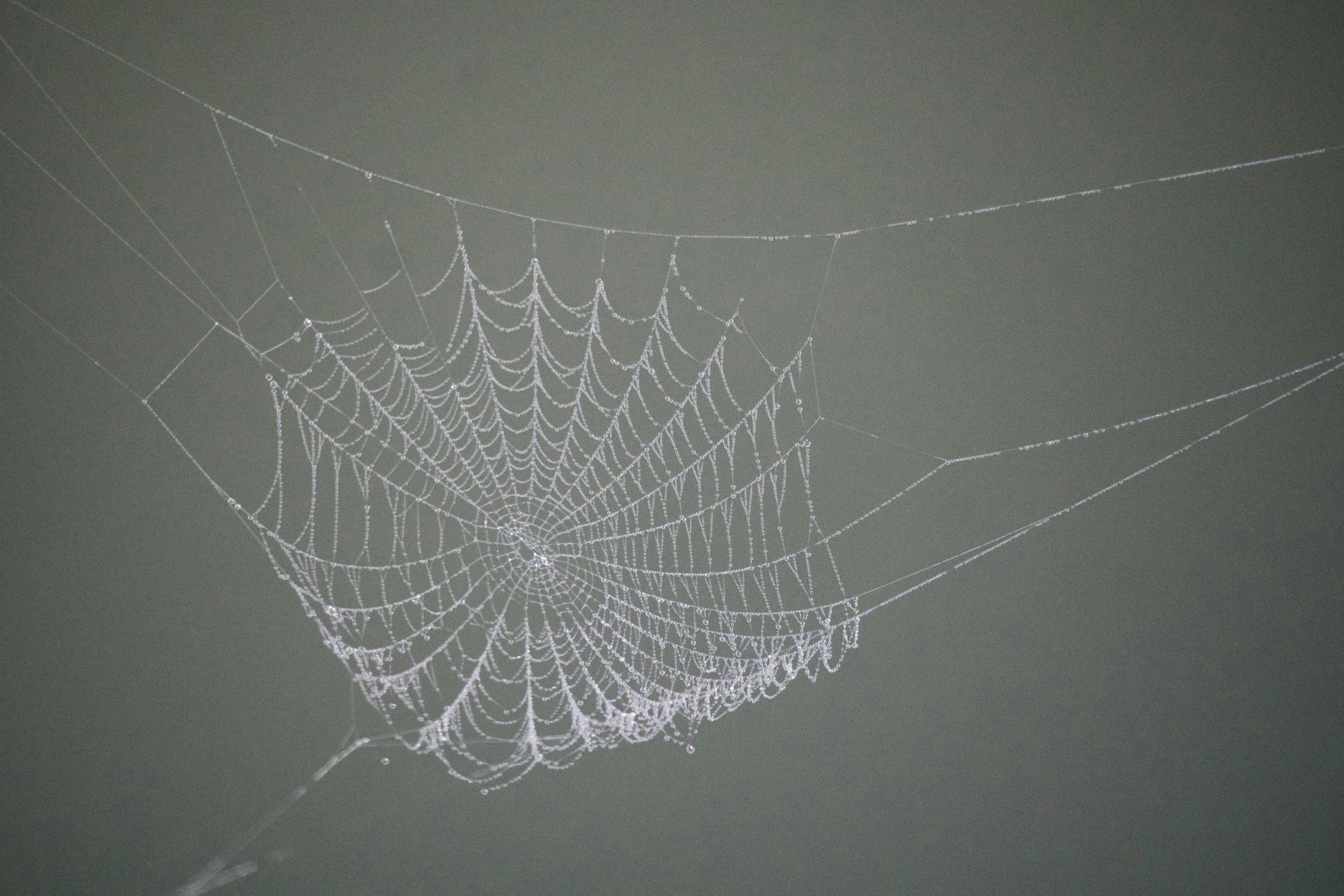

The main difference between scar tissue and healthy tissue is the arrangement of the collagen fibres: in uninjured tissue, these are arranged in a “basket weave” formation, which allows force to be distributed and transmitted evenly throughout the tissue; in a scar, the tissues arrange themselves in a single direction, which makes them less resilient. So if you keep spraining your ankle, that’s one of the reasons: the tissue has become weaker and is more likely to be re-torn (and nobody fully rehabs their sprained ankle appropriately, which is a pet peeve for another blog post someday).

Notice I used the example of a sprain, which I’m guessing is not what you imagined when you thought of a scar - I’m assuming you pictured a scar on the skin’s surface. The thing is, the scar on the surface is akin to the tip of an iceberg; in most injuries and surgeries, the scar tissue extends far beneath the surface of the skin - even in the case of arthroscopy or laparoscopy, in which the scars on the skin are very small, the instruments had to carve a path through various tissues to get to whatever organ or structure they were repairing, leaving scar tissue in their wake. Caesarean section scars are another powerful example: the scar on the skin is usually only 10-15cm, but it’s obvious they didn’t only cut through the skin…

So let’s talk about those other layers. I’m not going to bore you with the details of dermis, epidermis, superficial fascia, deep fascia, muscle, and so on; but it is important to note that we are made of layers of different tissues. Have you ever sliced through a cake with multiple layers? And watched as the bright jammy layer smears through the clean white creamy layer? Now imagine if you tried to put those two halves back together. You wouldn’t be able to match the layers perfectly; a little jam would be in the cream, a little cream would be in the jam, it would still be delicious of course but noticeably messier.

So, that’s not exactly what happens in our tissues, but essentially, once the bleeding has stopped and the emergency repair crew come in to merge the edges back together (I’m talking about the cells in your body, not the surgeon who stitches you up - although I guess this applies to them too), it’s a bit hard to cleanly match one layer back up to itself, so they do the best they can because ultimately, the important thing is to close the wound to prevent infection.

Ok, so you have a few sticky layers - so what? Well, our entire system is made to move. When we move, and the layers glide past each other, cells get the signal to make more hyaluronic acid (yes, the stuff in your face cream) which keeps everything lubricated. When tissues sense force coming through them, they receive the signal that those tissues need to be stronger (which is why weight-bearing and impact exercise create stronger bones, and why lifting heavy weight creates stronger muscles). So when the layer stick, and stop gliding, less hyaluronic acid get produced, and they get stickier - so the tissues directly around them can’t move freely, and they get less hyaluronic acid, and they get stickier - and so on. And if those layers make a big sticky lump, the force moves through them differently, so that’ll affect the tissues the force would normally have be distributed through - and any that end up taking on the extra load. So that’s why a small scar on your abdomen can end up causing shoulder pain, for example (without even getting into the biomechanics of it - because unlike many others in my field, I don’t actually think fascia is always the answer).

Where scars can become particularly problematic is when those sticky layers start to involve your organs; it’s not hard to see how your bladder or stomach getting stuck to the tissues around it could cause not only pain but limitations in how that organ functions. It may sound far-fetched, but a recent study found almost half of women experienced symptoms of caesarean scar disorder - including chronic abdominal pain, post-menstrual spotting and abnormal vaginal discharge - within the first three years post c-section.

So. What do we do about this?

Before I tell you what scar therapy is, let me tell you what it is not: it is not the painful friction you may have had done by a physiotherapist, or been told to do by your surgeon.

Scar therapy is gentle. So gentle it will feel like the therapist isn’t doing anything at all. This is intentional: the body has suffered a trauma, and it is going to be very protective of that wounded tissue. Pain will cause the tissue to contract which is the opposite of what we are trying to achieve.

Scar therapy is specific. We don’t just look at the scar on the surface of the skin and try to agitate it: we feel our way along it, gently, once you are able to tolerate touch on the scar (see above: this is not something we force - the body always lets us in when it’s ready - forcing it reminds me of what we used to to say about asking your Brazilian jiu jitsu professor about getting your black belt: every time you ask, they add another month). We identify the different textures of the scar: maybe some parts are raised, others are ropey, maybe some dip below the skin. We work each of those parts differently.

Scar therapy is holistic. I mean, this is something even the most basic massage qualifications teach (I would know: my first qualification ever was a 2-day Swedish massage certificate); you do something broad, then something specific, then back to broad. This is especially important in the case of scar therapy, as often people feel that their scars are “disconnected” from the rest of the body; sometimes they are numb, or painful to touch, or the person struggles to look at them. It is an important part of the treatment to “reconnect” the scar and the rest of the body and mind.

Scar therapy works with the body. I can’t say this enough, clearly. The body is always trying to protect itself and its status quo (i.e., homeostasis), and it remembers what it has suffered previously (I say body, you say mind, ultimately they are one and the same - we have sensors throughout our body communicating with the brain, which can in turn make us feel all sorts of things in our body - sadness, fear, a tummy ache, the need to pee when you are nervous - so interpret “the body keeps the score” however makes sense to you, but absorb the concept). If we do anything to the body that reminds it of a previous trauma, like stretching the edges of a scar when those edges have previously been pulled apart in a surgery, it is going to fight. And you will feel very uncomfortable. And I will see that I haven’t helped you at all. And then nobody is happy. Every technique of scar therapy involves feeling where the tissues want to go, and helping them go there - then the body finishes the job itself. The therapist is only there to guide - no God complex here.

What are the different approaches to scar therapy?

Some of you may have noticed I hold two scar therapy qualifications: Sharon Wheeler’s ScarWork and Restore scar therapy, which was developed by a former ScarWork practitioner. You’d think they would be more similar, but I was surprised by how different they were. These are my observations, in a nutshell:

Sharon Wheeler’s ScarWork is rooted in fascial release - it is somewhat esoteric, and in my opinion it resembles art more than medicine

Restore scar therapy encourages the use of devices such as cupping (manual and mechanical), taping, and the use of creams and gels - it aims to bridge the gap between the medical world and scar therapists

Sharon Wheeler’s ScarWork emphasises the integration of the scar with the rest of the body’s fascial network

Restore scar therapy emphasises the scar itself and, in particular, unsticking it from the layers beneath

Personally, I prefer the overall ScarWork approach, but a few of the techniques resonate with me more as they were taught by Restore. I feel I might split my time pretty evenly between techniques from the two approaches, but while the Restore techniques feel more understandable to the client, it’s the pure ScarWork techniques that give the most mind-blowing results. Ultimately, I don’t think any massage therapist having worked for over ten years is relying on a specific list of techniques - it’s like learning to drive; first you learn to pass the test, then you learn to actually drive.

If anyone has any experience of other types of scar therapy, or has any further thoughts on Sharon Wheeler’s ScarWork or Restore scar therapy or any other approaches - I would love to hear from you! And, as always, I am available to answer any and all questions - even if you are curious about scar therapy but can’t bear the idea of having your scar touched, or aren’t sure whether you would benefit from it, please do reach out so we can discuss how we could work together!